Natural disasters and pandemics: Supporting student and teacher wellbeing after a crisis

By Professor Helen Cahill, Dr Babak Dadvand, Keren Shlezinger, Katherine Romei and Anne Farrelly

This report presents an overview of research outlining effective approaches to the promotion of student and staff wellbeing during periods of emergency and recovery.

In recent months, Australia has experienced a series of catastrophic events, including the 2019–2020 bushfires, and the COVID-19 pandemic. The twin economic and health crisis resulting from both events has led to concerns about the wellbeing of children and young people who have experienced unprecedented disruptions to everyday life and exposure to traumatic events.

Teachers and schools often contribute as first responders in emergencies, and are adept at providing immediate care, despite themselves also being significantly affected by such emergencies. However, teachers often feel unsure about how best to provide psycho-educative support in the immediate aftermath and via longer- term recovery efforts.

This report presents an overview of research outlining effective approaches to the promotion of student and staff wellbeing during periods of emergency and recovery.

Exposure to emergencies such as bushfires and pandemics can be traumatic and cause major disruptions to families and to their livelihoods. Rates of family violence, sexual violence and mental health problems typically increase during and in the post emergency periods. During emergencies, women, girls and those already experiencing disadvantage are at much greater risk of violence and victimisation, and of the likelihood of developing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Emergencies disproportionately affect those already experiencing social or economic disadvantage, with poverty a major risk factor for increased risk of social, material and psychological harm. While most children and young people are resilient and recover well post emergency, some experience long-lasting mental health distress, including PTSD, anxiety disorders and depression. Common reactions that children and young people have include heightened anxiety even after the threat has gone, difficulty sleeping, difficulty concentrating on learning, problems with regulating behaviour and expressing emotions, challenges in managing frustration and conflict, anxiety about the effects on their own and their family’s future, and difficulties in getting along with others.

Earlier models of research investigating the wellbeing of those affected by emergencies focused on understanding the effects of direct exposure to the traumatic events. However, more recent research shows that distress can also be caused and intensified by high exposure to media recounting traumatic events, material deprivation, exposure to high levels of parental distress, and family violence. These stressors may be sustained once the immediate emergency has passed, with continued negative impact on children’s wellbeing and learning.

Research demonstrates that schools can make a major contribution to the prevention of mental health problems and to the promotion of resilience post emergency. Participation in sustained school-based social and emotional learning programs can help to mitigate the mental health effects of exposure to traumatic events, and lead to reduced rates of depression, anxiety and post traumatic stress disorder. They also help students to develop the key life skills needed to deal with the stressors and challenges of everyday life. These programs can also help schools fulfil their curriculum requirements in developing students’ personal and social capabilities, and benefit all students, regardless of their exposure to trauma.

A number of evidence-informed programs are available to guide teachers in adopting best practices both during the immediate aftermath of emergencies and in longer-term recovery. Schools can benefit from being made aware of existing teaching and wellbeing resources and services, and of the routine good practices they can continue to use effectively in the post emergency period.

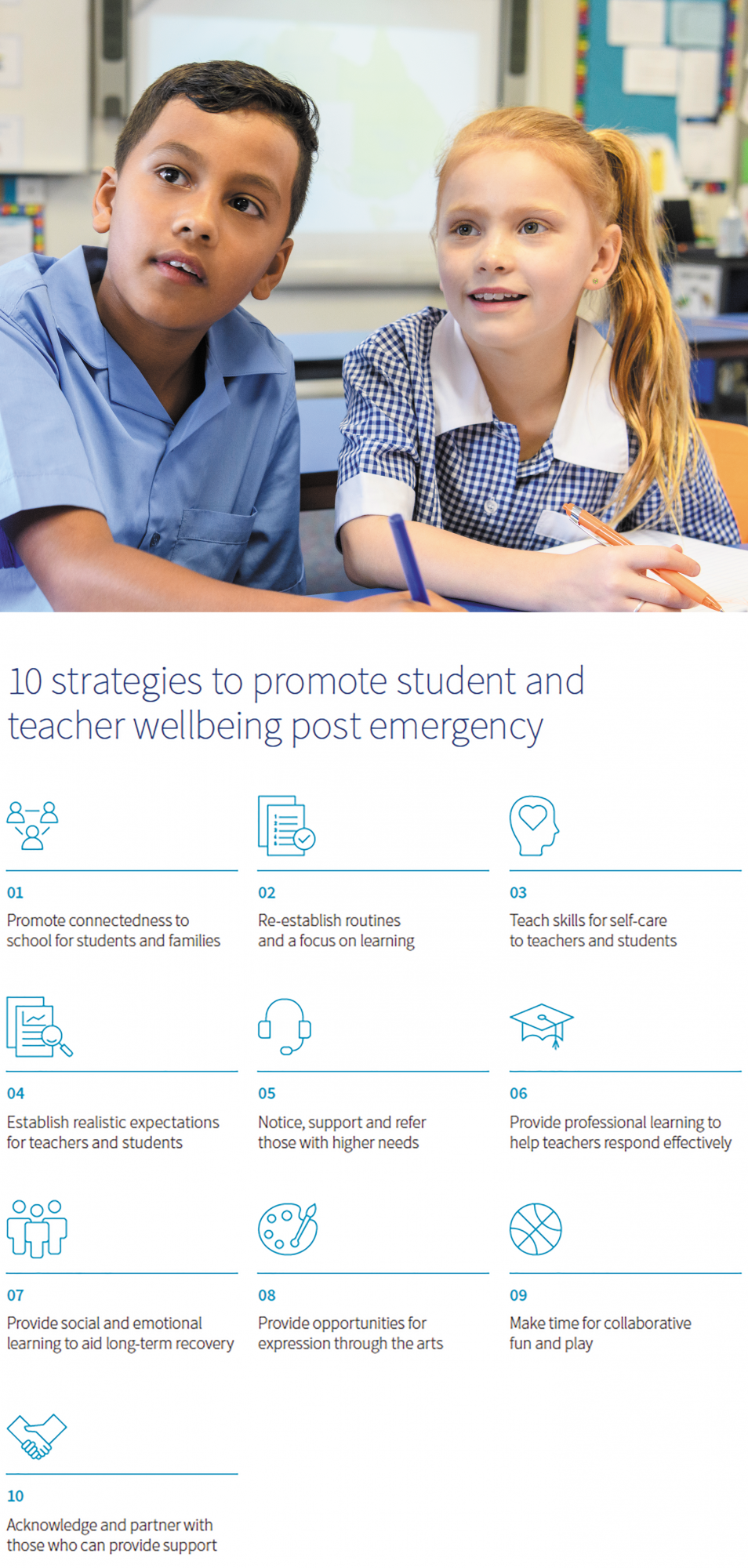

Schools benefit from clear guidance about effective response strategies to adopt post emergency. The following advice is derived from a summary of the available international research investigating effective approaches to promoting student wellbeing post exposure to a range of emergencies, including natural disasters, armed conflict and epidemics.

Several longitudinal studies have documented the way in which SEL initiatives provided in the primary years can have a lasting effect, promoting resilience and school connectedness well into the high school years. The most effective SEL programs are those that:

Risk factors associated with more severe or ongoing psychological distress after emergency situations may include:

For further advice visit the Australian Institute for Disaster Resilience website.