Future-proofing students: What they need to know and how educators can assess and credential them

By Enterprise Professor Sandra Milligan, Dr Rebekah Luo, Associate Professor Eeqbal Hassim & Jayne Johnston

Future-proofing our students so that they will have the skills to negotiate and thrive in increasingly complex global workplaces is a challenge for all educators.

Future-proofing our students so that they will have the skills to negotiate and thrive in increasingly complex global workplaces is a challenge for all educators. These crucial skills are often referred to as 21st-century skills, general capabilities, graduate attributes or transversal skills.

For students to thrive they need to become expert learners. They need to acquire a body of knowledge, skills, attitudes and values that enable them to adapt and contribute in an ever-changing environment.

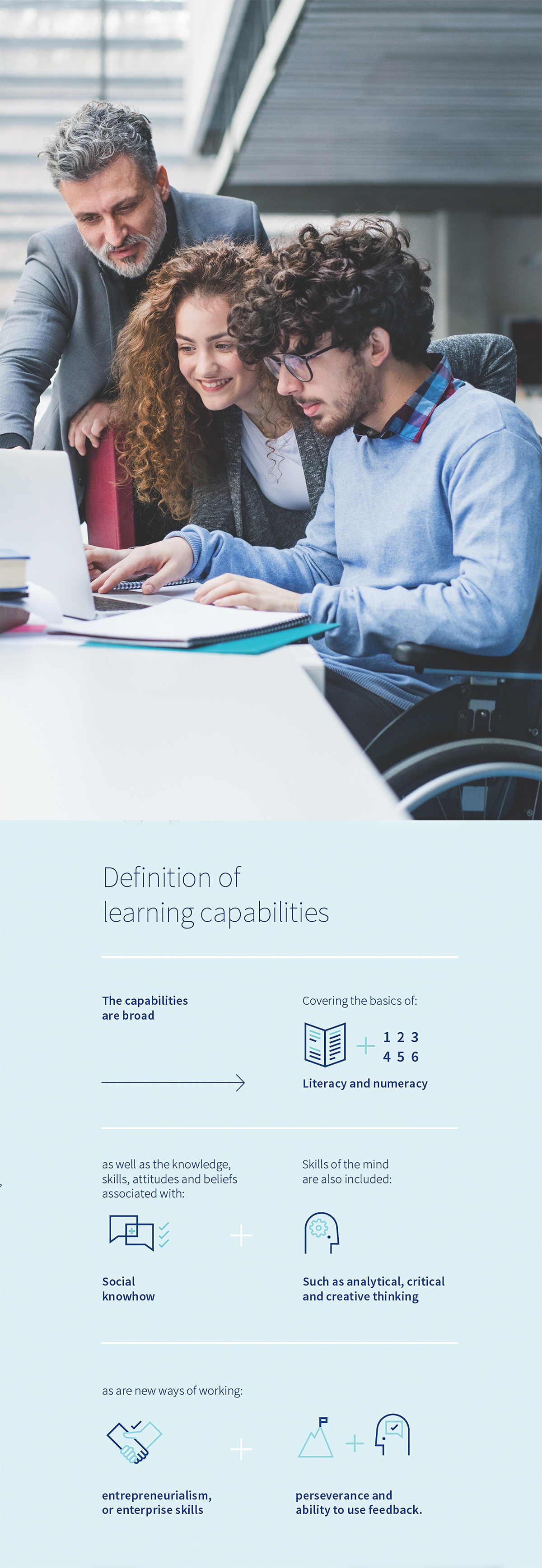

The skills, or capabilities for learning, include the basics of literacy, numeracy and the use of information and communication technology. More than this, they also encompass broader social skills of communication, collaboration and ethical behaviour and the ability to perform in an intercultural environment. Personal skills, such as persistence and the capacity to use feedback and analytical skills, such as computational thinking, creativity and criticality, are also paramount. Increasingly, the need for entrepreneurial and enterprise skills reflects the new ways of living, learning and working in the digital era.

Most education institutions and schools in particular, regard these skills or capabilities as being at the heart of their teaching. In fact, the capabilities for learning outcomes are now included in formal curriculum statements, both nationally and internationally. Debates ensue, however, about whether or not it is feasible to teach and assess these skills formally. What is clear is that these skills cannot be learned if learning is experienced only through carefully directed, broadcast-style instruction, targeting mastery of set texts and assessed using well-rehearsed written examinations that rely on individual, intellectually focused effort.

Future-proofing our students means ensuring that they learn a wide range of skills, or capabilities, that will allow them to thrive in increasingly complex global workplaces.

For learners to develop these skills or capabilities, the organisation of learning must provide students with the opportunities to truly exercise their capacities.

Authentic, challenging learning tasks are required, preferably ones that are relevant to and engaging for the learner and should be incorporated into teaching in any and all domains or fields of study, be these history, mathematics, plumbing, engineering, music or sport.

In order to upskill learners and to future-proof them, we need to assess these capabilities, offer feedback on how they are performing and report their progress to external stakeholders, such as parents and potential employers. The capabilities can be assessed directly and recognised alongside the more traditional assessments dealing with the mastery of content. There are professional challenges confronting those who do assess and recognise these capabilities, but practical techniques, perspectives and tools have been developed, as the case studies in this paper demonstrate.

Some organisations are already engaged in innovative teaching and assessment, particularly in secondary and post-secondary education and in the transition from school to work. But there are lessons for assessment and reporting that are applicable to any level of education, from early childhood to universities

and workplaces, so that learners can develop the essential, transferable skills needed for lifelong learning.

If the goal is to ensure that learners can master skills as part of their day-

to-day educational endeavours, it is simply not effective to play around the edges of current practice, with minor adjustments to teaching and assessment. What we need is deeper, more systematic change, starting with altering what and how we assess and we need it sooner rather than later.

Educators need support as they move to incorporate the use of transparent, trusted, comparable, moderated, developmental, performance-based assessments of students’ levels of attainment in learning capabilities, or skills, into their normal assessment and reporting practices. The following recommendations would enable the transition to a new system of assessment as outlined in this paper.

We need to develop a standards framework to assist teachers with making comparable assessments of learners’ levels of attainment in capabilities for learning.

We need to design a flexible reporting framework to assist educators to credential attainment and to provide common currency for reporting by Australian educators.

We need to provide moderation support to at least the same level provided for more traditional content areas in the curriculum.