Work

Links between work and study

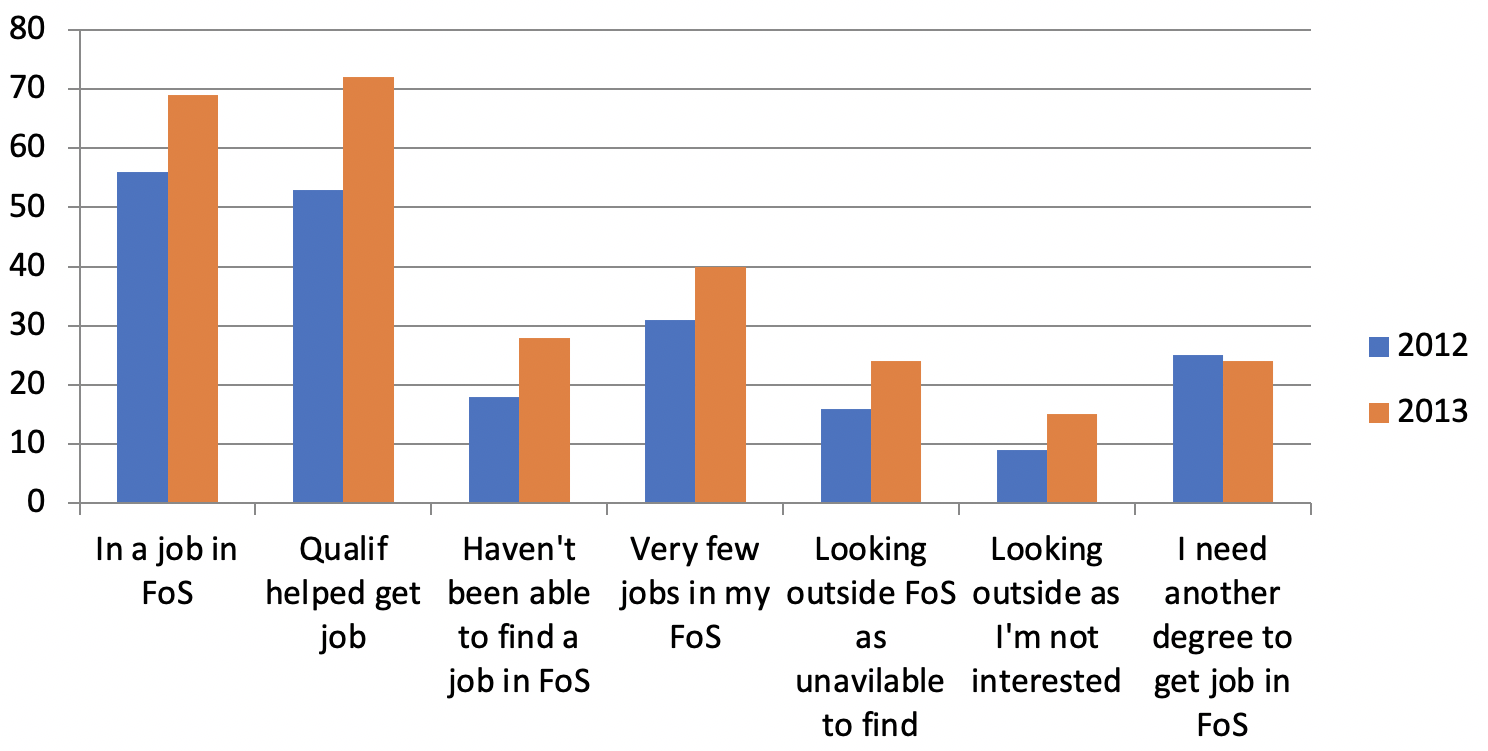

We examined young people aged between 23 and 25 between 2012 and 2013 to examine the link between study and work. The figure below shows that for approximately a third of participants, the quest to secure a job in their field of studies remains elusive. The results do show some positive signs in terms of the strength of the link between education and work. In the last two years there has been an increase of at least 10% of participants working in their field of study and of 15% who found a job that related to their education qualifications. However, there has also been almost a 10% increase of participants who are concerned with the scarce availability of work in their field of study and with those looking outside of their field because they cannot find a job.

Link between study and work, for Cohort 2, aged 23- 25, in 2012 – 2013 (%)

*FoS = Field of Study

Working conditions

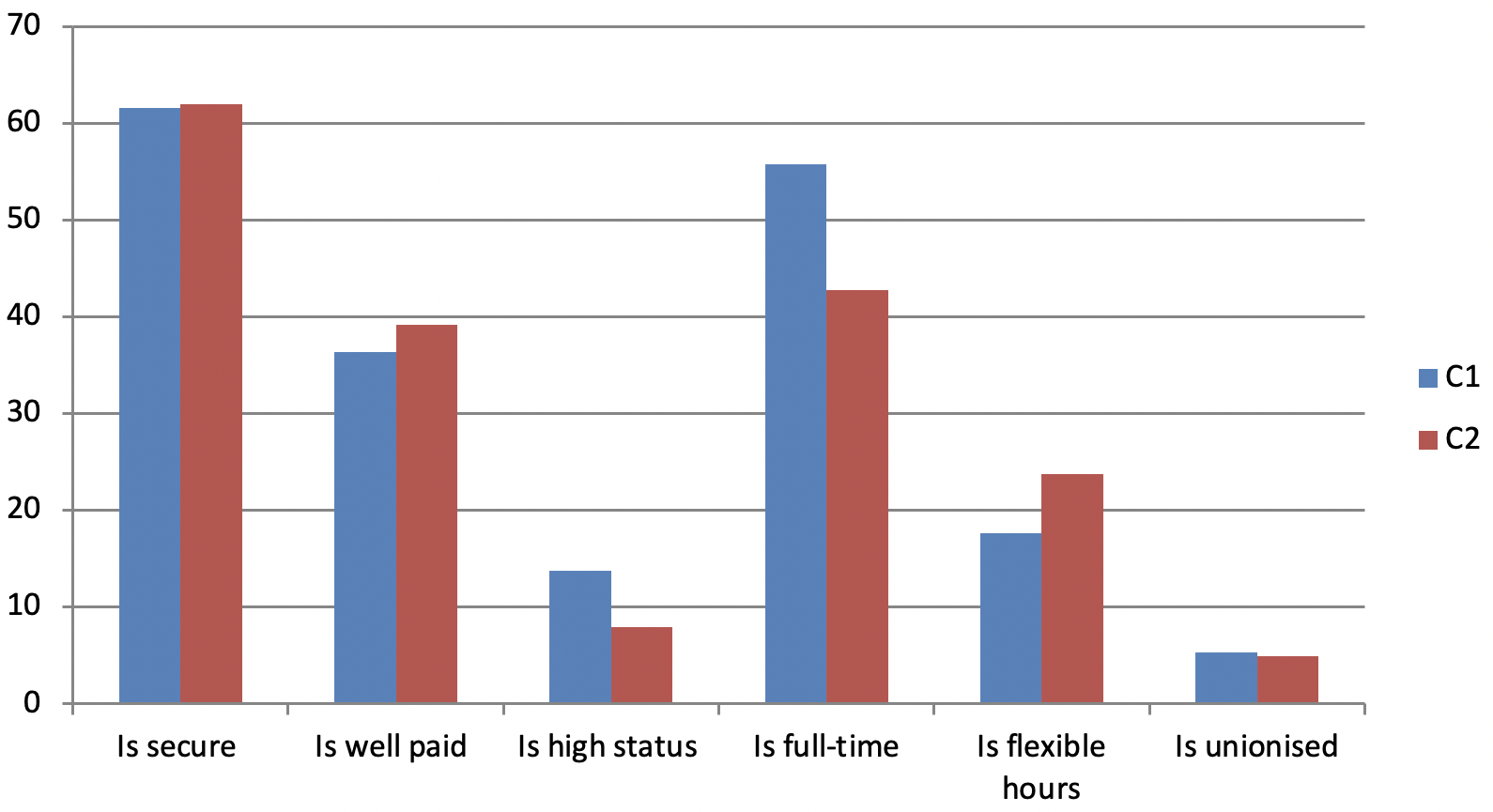

When they were aged 23, we asked both cohorts in 1996 and 2011 respectively, to rate the importance of conditions at the time of deciding on a job. Their responses reveal greater inter-generational similarities than differences and some of the differences are more a result of a different way of understanding and addressing the labour market. The figure below depicts their assessments of the conditions that are ‘very important’ for when deciding on a job for the future. It shows that security at work is paramount for both generations. However, compared to cohort 1, participants in cohort 2 place less emphasis on getting high status jobs and having full time work, and place more emphasis on job flexibility. This difference in the acceptance of ‘flexible hours’ by participants in Cohort 2 reflects Andres and Wyn’s (2010) assertion that young people are actively shaping their world and responding to uncertainty in the employment market. Further, Wyn and colleagues (2008) argue that unlike their parents’ generations, these young people valued horizontal mobility over the tradition upward social mobility of the past. Having the right set of dispositions and skills to move across industries has become as important as moving upwards in your employment sector or company.

Importance of the following in deciding on a job for the future, by ‘very important’, for both cohorts, aged 23, in 1996 and 2011, (%)

Non-standard hours

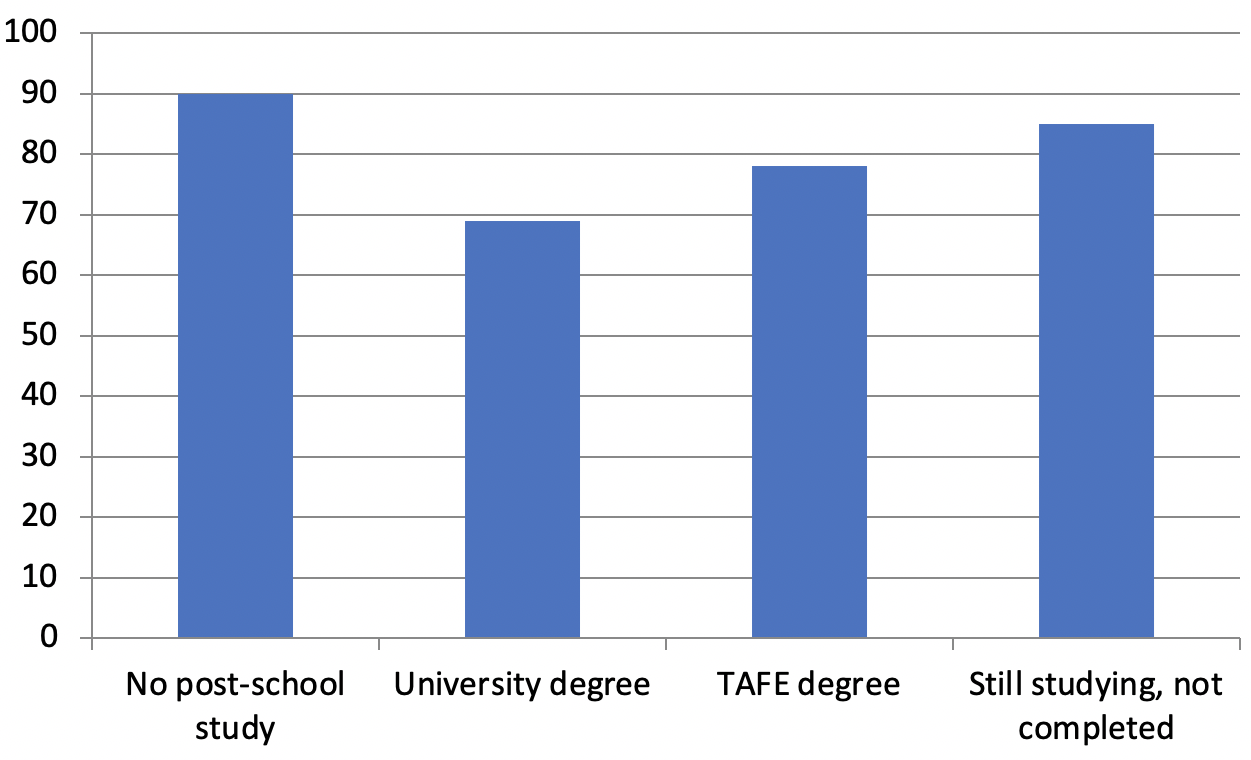

We also found that young people in Cohort 2 between the ages of 24 and 25 with a tertiary education credential are more likely to be working in jobs that do not involve irregular hours than those that do not have this qualification. Nonetheless, the percentage is still high: almost 70% of participants holding a university degree are working on weekends, evenings or public holidays. The level of education is not the only variable that affects the likelihood of having to work irregular hours. The type of work and industry an individual does have also an impact on employment. Young people working in the hospitality sector and retail (96%), in skilled trades (88%) and creative industries (e.g. music, publishing, journalism) (84%) were more likely to be doing non-standard shifts than those in education and health sector (60%), in administrative and business jobs (56%) and in professional (e.g. lawyers, accountants) jobs (70%). Beyond the different variables and aspects of the labour market and education that might affect the type, quality and mode of work, one thing is clear: the employment trend from previous generation standard week of work of 40 hours from Monday to Friday 9 to 5 is almost a thing of the past

Non-standard shifts by level of education, for Cohort 2, aged 24-25, in 2013, (%)

You can read more about young people and their labour market conditions in our report ‘Generational insights into new labour market landscapes for youth’ by Hernán Cuervo, Jessica Crofts & Johanna Wyn, which can be accessed here